| Numéro |

Sci. Tech. Energ. Transition

Volume 80, 2025

Emerging Advances in Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems and Integration

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Numéro d'article | 11 | |

| Nombre de pages | 24 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.2516/stet/2024101 | |

| Publié en ligne | 20 janvier 2025 | |

Regular Article

Navigating the energy crisis: automakers’ coopetition strategies under dual credit policy

1

School of Business Administration, Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, Guiyang 550025, Guizhou, China

2

Guizhou Vocational College of Economics and Business, Duyun 558022, Guizhou, China

3

Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities, Duyun 558000, Guizhou, China

* Corresponding author: wangchj828@mail.gufe.edu.cn

Received:

21

August

2024

Accepted:

13

November

2024

To tackle the energy and climate crises and achieve sustainable development, China has designated the development of new energy vehicles (NEVs) as a national strategy. This paper delves into the coopetition strategy of dual-model automakers under the dual credit policy (DCP) using a subsidy-R&D-production three-stage game model, considering government subsidies and consumer preferences. The model explores various strategies, including full competition and different R&D cooperation scenarios for fuel vehicles (FVs) and NEVs. Key findings include: (1) R&D subsidies boost NEVs R&D investments but may not always optimize social welfare. (2) When NEVs technology spillovers are low, firms should fully cooperate; otherwise, the FVs R&D cooperation is optimal, especially with high FVs spillovers. (3) Investments and outputs in both vehicle types positively correlate with technology spillovers, and consumer preferences. Conversely, FVs equilibrium decreases with NEVs credit proportion and fuel consumption disparities. (4) The credit price positively influences R&D investments and outputs of NEVs, but its effects on FVs’ R&D investments, outputs, corporate profits, and social welfare vary based on market dynamics. Recommendations include optimizing subsidy policies, supporting low-carbon FVs, enhancing infrastructure, and strengthening DCP regulations to stabilize credit price expectations.

Key words: Dual credit policy / Government subsidies / Coopetition strategies / R&D investments / Consumer preference / Technology spillovers

© The Author(s), published by EDP Sciences, 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1 Introduction

Currently, the global energy shortage is becoming increasingly severe, and extreme weather events are occurring more frequently, posing a serious threat to sustainable development [1]. In response to these challenges, governments worldwide are taking action. Notably, China, as a prominent and responsible major power, has established the 3060 Strategy. Benefiting from government financial support, the new energy vehicle (NEV) industry has achieved rapid development as a crucial component of this ambitious strategy. However, with the emergence of fraud and rent-seeking behaviors, the government has shifted its policy focus towards market-based mechanisms. The “Parallel Management Regulation for Corporate Average Fuel Consumption (CAFC) and NEV Credits for Passenger Cars” (Dual Credit Policy, DCP) has emerged and become the predominant policy driving industrial development [2]. The DCP exerts a significant influence on both fuel vehicles (FVs) and NEVs through its structured implementation of CAFC credits and NEV credits. By mandating that traditional automobile manufacturers improve their fuel efficiency metrics and adopt advanced technologies for electrification, the DCP creates a compelling regulatory framework that necessitates innovation within the automotive sector. As manufacturers strive to meet the increasingly stringent fuel efficiency standards, they are prompted to invest heavily in research and development aimed at optimizing internal combustion engine performance, integrating lightweight materials, and enhancing overall vehicle design. Concurrently, the introduction of NEV credits serves as a catalyst for the transition towards electric mobility, compelling manufacturers to expand their electric vehicle portfolios and adopt cutting-edge battery technologies. However, the DCP’s stringent requirements and incentives have also resulted in heightened competition among automotive producers, as both established firms and emerging startups vie for market share in the burgeoning NEV segment [3].

To maintain their competitive advantage, automakers must continuously strengthen their technological innovation capabilities [4]. However, technological innovation activities are characterized by large investments, long cycles, high risks, and technological spillovers [5, 6]. Consequently, it is challenging to effectively navigate the increasingly fierce market competition independently. As a result, collaboration among competitors has increasingly emerged as a prevalent phenomenon in corporate operations [7–13]. For instance, in 2017, CCAG (China Changan Automobile Group) signed a strategic cooperation framework agreement with FAW (First Automobile Works) and DFMC (Dongfeng Motor Corporation) to collaborate on mutual technological innovation. Similarly, in 2019, SAIC (Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation) and GAC (Guangzhou Automobile Corporation) established a strategic cooperation agreement to jointly leverage industry chain resources and engage in R&D cooperation focused on NEVs, artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, and lightweight materials. Additionally, in 2023, Geely and CCAG announced a strategic partnership aimed at platform sharing and technological R&D for both FVs and NEVs, with the objective of optimizing their respective strengths through integrated resource management.

Undoubtedly, while these firms engage in collaborative efforts to share and complement each other’s strengths in automotive technologies, they still maintain a competitive relationship in their core businesses [14, 15]. The DCP plays a pivotal role in shaping the automotive industry’s development trajectory by driving improvements in fuel efficiency for FV and promoting the research and development of NEV technologies, thereby enhancing battery performance and extending range capability. Therefore, companies must address several practical issues, including whether to collaborate on FVs and NEVs under the DCP, how to clearly define the scope of their cooperation, and what competitive strategies to implement.

R&D subsidies serve as crucial governmental instruments to rectify market failures in innovation [16]. Technology spillovers, a key facet of R&D externalities, enable competitors to benefit from technological advancements without bearing any costs, whereas innovative companies may find it difficult to obtain corresponding returns, thus affecting their enthusiasm for R&D investment [6, 17]. In response, scholars advocate adopting competitive and cooperative strategies alongside R&D subsidies to address these market inefficiencies. However, despite the efforts made by enterprises in R&D competition and cooperation, R&D inventments are still unsatisfactory [18, 19], which highlights the need for continued government subsidies for R&D [20]. Consequently, under government subsidy policies, particularly within the framework of the DCP, determining the optimal competitive strategy becomes a critical strategic consideration for automakers.

Consumer preferences for low-carbon options and range capabilities play pivotal roles in shaping firms’ technological innovation trajectories and significantly influence their R&D and production strategies [21]. The growing environmental awareness among consumers is increasingly recognized as a catalyst for technological progress. Presently, consumers are highly concerned about environmental issues and are willing to pay a premium for high energy-efficiency FVs and NEVs [22–24]. This conscientious consumer behavior spontaneously contributes to social green development goals [25]. However, challenges such as limited range and insufficient charging infrastructure remain critical barriers to the widespread adoption of NEVs [26–28]. Due to the long construction period of charging infrastructure and the involvement of multiple stakeholders, solving these problems – especially improving the range capability in the short term – is crucial to increasing consumers’ willingness to adopt NEVs [29, 30]. Since consumers’ low-carbon and range preferences significantly impact demand, effectively assessing these preferences is crucial for automakers to formulate cooperation strategies under the DCP. This assessment not only improves the accuracy of automobile manufacturers’ market forecasts and informs their R&D and production decisions, but also optimizes the applicability of DCP.

In view of this, this study aims to explore the coopetition strategies of automakers taking into account subsidies and preferences under the DCP and primarily solves the following problems: Firstly, What impact does the DCP have on FVs and NEVs, and how to modify and improve it? Secondly, how should the government determine the subsidy rate within the framework of the DCP to maximize social welfare? Thirdly, what cooperation strategies should companies adopt under the DCP when considering subsidies and consumer preferences? Lastly, how do critical factors such as the DCP, technology spillovers, and consumer preferences for low-carbon and range capabilities influence firms’ optimal strategies?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 comprises the literature review. Section 3 introduces the related assumptions and develops the models. Section 4 is the model solution. In Section 5, our focus is on the selection of optimal strategies. Section 6 conducts an analysis of impact factors. Section 7 presents the discussion. Finally, Section 8 summarizes the findings, provides policy recommendations, and proposes directions for future research.

2 Literature review

The studies related to this paper focus on four main aspects: the DCP, firms’ coopetition strategies, the impact of subsidies on the R&D investments, and the impact of consumers’ low-carbon and range preferences.

2.1 The DCP

As a sustainable development policy in emerging markets, the DCP achieves energy savings and emissions reduction goals in the automotive industry [31], while also significantly promotes the development of the NEV industry [32]. Since its implementation, relevant studies have primarily focused on evaluating and comparing the DCP [33, 34], as well as on the production decision-making of automobile firms [35, 36]. For instance, Cheng and Fan [3] investigated the production and operational strategies of both FVs and NEVs manufacturers competing under the DCP framework, finding potential negative impacts on the automotive supply chain performance. Although the DCP has demonstrated potential in promoting sustainability objectives, certain research indicates that it may have unintended consequences on supply chain performance. The automotive sector’s sustainable transformation is still the subject of ongoing research as researchers endeavor to comprehend the policy’s intricate effects on market dynamics, technological innovation, and industry structure.

The current literature on R&D subsidies under the DCP is relatively sparse, with only a handful of studies addressing this intersection. Lu and Yan [37] examined the implications of credit trading and compared equilibrium outcomes in R&D competition and cooperation among duopolistic NEVs firms, yet did not delve into government subsidies or consumer preferences. Zheng et al. [38] developed a three-stage vertical supply chain game model involving NEVs suppliers and manufacturers to explore the effects of R&D subsidies, but overlooked considerations of consumer preferences and horizontal competition. Wang et al. [39] conducted research on the production decisions of a single automaker, primarily focusing on consumers’ low-carbon preferences. However, their study did not include an analysis of consumers’ range preferences or the dynamics of horizontal competition within the automotive supply chain.

2.2 Firms’ coopetition strategies

Research on corporate coopetition strategies has attracted widespread attention from global academic circles. D’Aspremont and Jacquemin [40] were pioneers in developing the foundational analytical framework for the R&D cooperation game. They conducted a comparative analysis of R&D investments and output among duo-oligopoly firms that produce homogeneous products, and explored the impact of of R&D competition and R&D cooperation in the context of technological spillovers. Their work introduced the influential AJ model, which has since shaped the study of corporate cooperation. Recognizing the limitations inherent in the duo-oligopoly assumption, Suzumura [41] extended this framework to encompass scenarios involving multiple oligopolies. His research validated the AJ model’s findings across a broader spectrum of conditions, thus reinforcing its theoretical robustness. Subsequently, Kamien et al. [18] extended the AJ model by examining the impact of product differentiation and firm organizational structure. They concluded that fostering R&D cooperation, particularly in environments characterized by technological spillovers and shared R&D outcomes, can optimize firm profitability. Thereafter, Atallah [42] examined the influence of horizontal and vertical spillovers on firms’ R&D investments under different organizational models. His study highlighted that the vertical R&D cartel model tends to attract the highest level of R&D investments. However, technological investment is a necessary condition for technological spillover, while absorptive capacity constitutes a sufficient condition for technological spillover. The literature above does not consider absorptive capacity, nor does it focus on the automotive sector influenced by industrial policy and consumer preferences.

The implementation of DCP has had a significant impact on the automobile industry, and automobile manufacturers need to adjust their R&D and production strategies according to policy changes. Based on cross-chain cooperation, Li et al. [43] investigated how the dual credit policy and subsidy policy affect production decisions among manufacturers of FVs and NEVs. Huo et al. [44] examined credit trading strategies and cooperation tactics within the supply chain involving FVs and NEVs manufacturers and dealers, taking into account consumer sensitivity to fuel consumption and range capabilities. However, the strategies discussed in the literature above primarily focus on credit trading mechanisms and overlook the competitive dynamics related to technological innovation.

Significantly, Yuan et al. [45] analyzed the strategic selection in R&D as well as production stages between competition and coopetition among duopoly heterogeneous manufacturers of NEVs under the DCP. Their study takes into account factors such as R&D subsidies and consumers’ range preferences. However, their research focuses exclusively on coopetition strategies among NEV manufacturers, overlooking dual-model companies engaged in both FVs and NEVs production. The automotive sector, especially for dual-model automakers, is influenced by factors from both the supply and demand sides. The R&D efforts not only affect the efficacy of DCP and subsidy, but also enhance consumer preferences for low-carbon and range capabilities. Simultaneously, they collectively impact automakers’ R&D investments, production decisions, and competitive strategies compared to traditional industries. Existing literature lacks studies on the coopetition strategies from this perspective, our forthcoming research aims to significantly extend these findings.

2.3 The impact of subsidies on the R&D investments

Firms’ R&D investments are often accompanied by the issue of government subsidies. Bronzini and Piselli [46] highlighted that these subsidies typically yield a positive impact on firms’ innovation efforts. Similarly, You and Zhu [47] developed a three-stage dynamic game model to study the impact of R&D subsidies under different competition frameworks – R&D competition, R&D cartel, and Research Joint Venture (RJV) cartel. Their analysis highlights the significance of government subsidy policies in optimizing firms’ technology innovation investments. Furthermore, Chen et al. [48] provided empirical insights into how R&D subsidies and non-R&D subsidies affect the Initial Public Offering (IPO) performance of entrepreneurial firms. They observed an inverted U-shaped relationship between R&D subsidies and IPO performance, indicating that while moderate levels of R&D support enhance performance, excessive subsidies might not yield commensurate benefits. On the other hand, non-R&D subsidies were found to consistently boost IPO performance, illustrating their positive impact on firms. It is important to note that the literature reviewed predominantly focuses on traditional industries and lacks exploration of the NEVs industry.

In relation to the impact of government subsidies on R&D investments in NEVs, several studies contributed significant insights. Gao and Hu [49] argued that governmental financial support notably enhances the performance and size of firms, as well as their patent output. Cao et al. [50] discovered that heightened levels of government funding facilitate automobile manufacturers in surmounting technical barriers, achieving innovative breakthroughs, scaling the NEV industry, and fostering consumer adoption. Liu and Xiao [51] examined the development of electric vehicles under policy incentives using a system dynamics model of DEA. Their results show that the market penetration rate of electric vehicles in China is mainly affected by national policies, and the combination of various subsidy policies has become the best strategy to stimulate the NEV market. Wu et al. [52] conducted an empirical analysis on the impact of government R&D subsidies on innovation among Chinese firms. The study revealed that firms with advanced technological capabilities tended to favor collaborative R&D, whereas those with lower technological capabilities opted for internal R&D. It is notable that the aforementioned scholars examined the effects of subsidy policies from various perspectives, yet they did not take account for the influence of the DCP, a predominant industrial policy.

2.4 The impact of consumers’ low-carbon and range preferences

With the escalation of environmental issues, more and more consumers are spontaneously paying attention to the fuel efficiency of FVs. Currently, numerous scholars integrate consumer preferences for low-carbon options into research on supply chain decision-making. For instance, Du et al. [53] discussed the impact of consumers’ low-carbon preferences on supply chains that focus on carbon emissions. Similarly, Ji et al. [54] investigated pricing strategies and emission reduction decisions in dual-channel supply chains considering consumer low-carbon preferences. Based on a carbon cap-and-trade system, Peng et al. [55] studied decision-making under uncertain returns, especially considering preferences for low-carbon influences. As consumers’ awareness of low-carbon and environmental protection increases, people’s willingness to pay a premium for low-fuel consumption products continues to increase [56]. Hence, the incorporation of consumer low-carbon preferences into models becomes increasingly imperative and realistic.

Regarding the influence of consumer range preferences, numerous scholars have underscored the pivotal role of range in consumer decision-making [26, 57, 58]. Avci et al. [26] identified that concerns over mileage anxiety due to limited range and insufficient charging infrastructure severely restrict the adoption. Lim et al. [58] explored how consumer concerns regarding mileage and resale value impact the widespread adoption of NEVs. Consumer preferences for NEVs are shaped not only by demand-side factors like range but also by supply-side government policies in the automotive industry [59]. However, existing literature predominantly confirms empirically the constraining effect of range without delving deeper into how consumer range preferences influence automakers’ R&D investments, profits, and social welfare. Moreover, these studies do not account for the impact of the DCP. In reality, with the DCP dominating industry development, automobile firms can only achieve sustainable and strong growth by improving the fuel efficiency of pure electric vehicles and the range capabilities of NEVs through continuous R&D innovation and technological upgrading.

Overall, some scholars have confirmed that the fuel consumption level of FVs and the range of NEVs are crucial factors influencing consumer adoption. Yet, little research explores how consumer preferences for low-carbon and range influence the selection of coopetition strategies. Moreover, studies examining the combined effects of both factors are scarce. In contrast to prior research, this paper systematically investigates the selection of coopetition strategies between two dual-vehicles manufacturers, taking into account subsidies and consumer preferences under the DCP. It offers policy recommendations and managerial insights from governmental and corporate perspectives to promote the high-quality development of Automobile industry.

3 Model assumptions and construction

Current research on the automotive industry’s development under the DCP typically focuses on scenarios with a single manufacturer producing either FVs or NEVs, or two manufacturers specializing separately in FVs and NEVs. However, these studies often overlook the combined impacts of the DCP, subsidy policies, and consumer preferences. Therefore, this paper concentrates on two dual-vehicles manufacturers that produce both FVs and NEVs, such as SAIC, Geely, and Great Wall, which are enhancing their fuel technology while accelerating their transition to electrification. In this context, the paper develops a three-stage game model involving subsidies, R&D, and production decisions between the government and two dual-vehicles manufacturers under the DCP. It examines how these manufacturers make decisions of R&D and production, as well as their competitive strategy, considering R&D subsidies and consumer low-carbon and range preferences. The supply chain system structure is shown in Figure 1.

|

Fig. 1 The supply chain system structure. |

The DCP stipulates the necessity of emission reduction for FVs and range enhancement for NEVs. Accordingly, this paper assumes that R&D for FVs is aimed at improving fuel efficiency, while R&D for NEVs focuses on range enhancement. When consumers have Low-Carbon and range preferences, referencing Peng et al. [55] and Zhou et al. [60], the inverse demand function for NEVs and FVs can be expressed as: (1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

Among them, a represents the automobile market size; θ denotes the proportion of potential demand for NEVs; pei (pfi) and qei (qfi) symbolizes the market clearing price and demand of NEVs (FVs), respectively; xei (xfi) signifies the innovative achievements of NEVs (FVs), which reflect in the degree of improvement in range (fuel efficiency). ηi (βi) indicates the level of technology spillovers of NEVs (FVs). Obviously, these values should satisfy 0 < ηi(βi) ≤ 1. Due to the existence of spillover effects, the R&D achievements of one firm can also promote those of its competitors, but the extent of this promotion depends on the absorption capacity of the other party. h(g) represents the coefficient of consumers’ range preference (low-carbon preference). A higher value indicates stronger consumer preferences, meaning consumers are willing to pay higher prices for NEVs (FVs) with strong range (higher fuel efficiency). Here and below, i, j = 1, 2 and i ≠ j.

Set the unit production cost of NEVs (FVs) as cei (cfi). Currently, the production cost of FVs is generally lower than that of NEVs, i.e., cei > cfi. Without loss of generality, we standardize cfi to 0, using c to indicate cei, and obviously θa > c. To obtain NEV (FV) innovative achievements xei (xfi), both automakers must incur the R&D cost  (

( ). Therefore, xei (xfi) can measure the level of R&D investments in NEVs (FVs). γ (γ > 0) represents the coefficient of R&D efficiency, and a larger γ indicates lower R&D efficiency. The amount of government subsidy provided to NEVs automakers is

). Therefore, xei (xfi) can measure the level of R&D investments in NEVs (FVs). γ (γ > 0) represents the coefficient of R&D efficiency, and a larger γ indicates lower R&D efficiency. The amount of government subsidy provided to NEVs automakers is  , where s ∈ [0, 1] denotes the subsidy rate.

, where s ∈ [0, 1] denotes the subsidy rate.

The second revised version of the DCP clarifies the calculation rules for NEV credits and CAFC credits. According to the updated guidelines, NEV credits are determined by subtracting the standard credits from the actual credits. Essentially, the value of NEV credits correlates positively with the driving range. If the market price of NEV credits is p0, the accounting coefficient of NEV credits is n, and the required proportion of NEV credits is λ, then the income from NEV credits for the firm Mi can be expressed as: p0(n(xei + ηixej)qei − λqfi). Similarly, the calculation rule for CAFC credits is based on the difference between the firm’s average fuel consumption target and the actual consumption, multiplied by the production quantity or import quantity of passenger cars. Setting the government-mandated compliance value as δ, the initial fuel consumption value per 100 km is φ, and after technological innovation, the fuel consumption value per 100 km becomes φ − xfi − βjxfj. To ensure that the DCP effectively regulates FVs, it is assumed that even after R&D, the fuel consumption level of FVs still does not meet the standard. Relaxing this assumption does not affect the study’s conclusions. Then, the negative CAFC credits of the firm Mi can be described as (δ − φ+ xfi + βjxfj)qfi. The cost of purchasing the NEV credits to offset the negative CAFC credits is p0(φ − δ − xfi − βjxfj)qfi, denoted as p0(μ − xfi − βjxfj)qfi. For the sake of computational simplicity, this paper solely concentrates on the symmetric solution, i.e., η(β) = ηi(βi) = ηj(βj).

In summary, the profit function of the firm Mi can be described as: (3)

(3)

The first term in equation (3) represents revenue generated from the production of NEVs. The second term denotes revenue from the production of FVs. The third term accounts for revenue from the sale of NEV credits. The fourth term reflects the cost incurred in purchasing NEV credits to offset negative average fuel consumption credits. The fifth term encompasses R&D costs for NEVs, net of government subsidies. Finally, the sixth term represents R&D costs for FVs.

Consumer surplus can be expressed as  , then the social welfare function can be defined as: consumer surplus + producer surplus − government subsidy, that is:

, then the social welfare function can be defined as: consumer surplus + producer surplus − government subsidy, that is: (4)

(4)

The above model parameters and the meaning of the symbols are shown in Table 1.

Model parameters and symbol definitions.

4 Model solution

In market economies, where cooperation among firms in the production phase is prohibited, our focus is exclusively on cooperation in the R&D stage. Firms are categorized into four strategic types based on the collaboration of dual-vehicle automakers in R&D for both FVs and NEVs. The first strategy, full competition (Strategy D), involves firms competing in R&D for both FVs and NEVs, exemplified by Great Wall Motors and FAW Group. The second strategy, partial cooperation focused on FVs R&D (Strategy J), entails collaboration in R&D for FVs while competing in NEVs R&D, as seen in the partnership between Geely and Renault. The third strategy, partial cooperation for NEVs R&D (Strategy R), involves competing in FVs R&D while collaborating in NEVs R&D, as demonstrated by Changan Automobile and GAC Group. Lastly, the full cooperation (Strategy C) strategy features firms collaborating on R&D efforts for both FVs and NEVs, illustrated by the collaboration between Geely and Changan. Given that both government and firms are aware of the game’s stage interactions, this dynamic process constitutes a three-stage game with complete information, amenable to resolution through backward induction.

Regardless of the strategy adopted by the enterprises, their problem-solving processes during the production phase are the same. That is to say, in the third stage, based on the government subsidy rate and the firms’ R&D investments, both parties determine output levels to maximize their individual profits. Specifically, each firm Mi determines the outputs of both NEV ei and FV fi. By substituting equations (1) and (2) into equation (3), the firms calculate the optimal outputs as follows: (5)

(5)

The Hessian matrix of equation (5) with respect to qei and qfi is denoted as ![$ {H}_1=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}}{\partial {q}_{{ei}}^2}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}}{\partial {q}_{{ei}}\partial {q}_{{fi}}}\\ \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}}{\partial {q}_{{fi}}\partial {q}_{{ei}}}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}}{\partial {q}_{{fi}}^2}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}-2& 0\\ 0& -2\end{array}\right]$](/articles/stet/full_html/2025/01/stet20240285/stet20240285-eq10.gif) . Obviously, H1 is a negative definite matrix and there exists a unique optimal output. By setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (5) with respect to qei and qfi equal to 0, we obtain the output of firm Mi as follows:

. Obviously, H1 is a negative definite matrix and there exists a unique optimal output. By setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (5) with respect to qei and qfi equal to 0, we obtain the output of firm Mi as follows: (6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

Proposition 1:  ). If

). If  ); otherwise,

); otherwise,  .

.

Proposition 1 posits that increased R&D investments in NEVs (FVs) enhances their respective output. However, due to the existence of competition, whether it is NEVs or FVs, low levels of technology spillovers lead firm’s output to decline as competitor’s R&D investments increase; conversely, output increases with higher levels of competitor’s R&D investments.

This is because, the R&D investments of firm Mj influences Mi’s equilibrium output through the technology spillover effect in a dual manner. On one hand, firm Mj’s R&D investments makes it profitable to expand the production scale of NEVs (FVs) by improving its range (fuel efficiency), which has a negative impact on the output of firm Mi; on the other hand, the R&D investments of firm Mj can improve the range (fuel efficiency) of firm Mi through technological spillovers, which has a positive impact on the output of firm Mi. When technology spillovers are limited, the negative impact predominates, resulting in a dampening effect. Conversely, greater technology spillovers amplify the positive impact, leading to a promotional effect.

4.1 Full competition (strategy D)

Under strategy D, the government determines the subsidy rate to maximize social welfare initially. In the subsequent stages, both firms engage in competition: first, deciding on their respective levels of R&D investments to maximize individual profits, and then competing in the product market for Cournot equilibrium output.

In the second stage, both firms following strategy D determine the optimal level of R&D investments to maximize their individual profits. By substituting equations (6) and (7) into equation (5), the profit function can be reformulated as follows: (8)

(8)

The Hessian matrix of equation (8) with respect to xei and xfi is as follows: ![$ {H}_2=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}^D}{\partial {x}_{{ei}}^2}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}^D}{\partial {x}_{{ei}}\partial {x}_{{fi}}}\\ \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}^D}{\partial {x}_{{fi}}\partial {x}_{{ei}}}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_{{Mi}}^D}{\partial {x}_{{fi}}^2}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}2(2-\eta {)}^2(h+n{p}_0{)}^2/9-\gamma (1-s)& 0\\ 0& 2(2-\beta {)}^2(g+{p}_0{)}^2/9-\gamma \end{array}\right].$](/articles/stet/full_html/2025/01/stet20240285/stet20240285-eq17.gif)

When conditions 9γ − 2(2 − β)2(g + p0)2 > 0, 9γ(1 − s) − 2(2 − η)2(h+ np0)2 > 0 are met, H2 forms a negative definite matrix, indicating the existence of an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (8) with respect to xei and xfi to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be obtained as: (9)

(9)

(10)

(10)

In the first stage, the government sets the optimal subsidy rate to maximize social welfare. This problem can be described as: (11)

(11)

Let ∂WSD/∂s = 0, the optimal government subsidy rate can be found to be: (12)

(12)

It is evident that the government subsidy rate increases in tandem with the level of technology spillovers of NEVs.

4.2 FVs R&D cooperation (strategy J)

Under strategy J, during the second stage, both firms collectively decide on R&D investments for FVs to maximize combined profits, while independently optimizing R&D investments for NEVs to maximize their respective profits.

In the second stage, the firm Mi determine xei to maximize respective profits, while both parties determine xfi to maximize their joint profits. Let  , the optimal R&D investments for both firms are determined as follows:

, the optimal R&D investments for both firms are determined as follows: (13)

(13)

(14)

(14)

The Hessian matrix of equation (13) with respect to xfi is ![$ {H}_3=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^J}{\partial {x}_{f1}^2}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^J}{\partial {x}_{f1}\partial {x}_{f2}}\\ \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^J}{\partial {x}_{f2}\partial {x}_{f1}}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^J}{\partial {x}_{f2}^2}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{2(5-8\beta +5{\beta }^2)(g+{p}_0{)}^2}{9}-\gamma & \frac{4(2-\beta )(2\beta -1)(g+{p}_0{)}^2}{9}\\ \frac{4(2-\beta )(2\beta -1)(g+{p}_0{)}^2}{9}& \frac{2(5-8\beta +5{\beta }^2)(g+{p}_0{)}^2}{9}-\gamma \end{array}\right]$](/articles/stet/full_html/2025/01/stet20240285/stet20240285-eq25.gif) . Simultaneously, the first and second order partial derivatives of equation (14) with respect to xei are:

. Simultaneously, the first and second order partial derivatives of equation (14) with respect to xei are:  .

.

Given the conditions 9γ − 2(5 − 8β + 5β2)(g + p0)2 > 0, 9γ(1 − s) − 2(2 − η)2(h + np0)2 > 0, (9γ − 2(1 + β)2(g + p0)2) (γ − 2(1 − β)2(g + p0)2) > 0, H3 is a negative definite matrix, along with  , there exists an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (13) with respect to xfi and equation (14) with respect to xei equal to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be obtained as:

, there exists an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (13) with respect to xfi and equation (14) with respect to xei equal to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be obtained as: (15)

(15)

(16)

(16)

In the initial stage, let ∂WSJ/∂s = 0, the optimal subsidy rate under strategy J can be determined as: (17)

(17)

4.3 NEVs R&D cooperation (strategy R)

Under strategy R, during the second stage, both firms collectively decide on R&D investments for NEVs to maximize combined profits, while independently optimizing R&D investments for FVs to maximize their respective profits.

In the second stage, we know that both firms determine the optimal R&D investments as follows: (18)

(18)

(19)

(19)

The Hessian matrix of equation (18) with respect to xei is![$ {H}_4=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^R}{\partial {x}_{e1}^2}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^R}{\partial {x}_{e1}\partial {x}_{e2}}\\ \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^R}{\partial {x}_{e2}\partial {x}_{e1}}& \frac{{\partial }^2{\pi }_M^R}{\partial {x}_{e2}^2}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\frac{2(5-8\eta +5{\eta }^2)(h+n{p}_0{)}^2}{9}-(1-s)\gamma & \frac{4(2-\eta )(2\eta -1)(h+n{p}_0{)}^2}{9}\\ \frac{4(2-\eta )(2\eta -1)(h+n{p}_0{)}^2}{9}& \frac{2(5-8\eta +5{\eta }^2)(h+n{p}_0{)}^2}{9}-(1-s)\gamma \end{array}\right]$](/articles/stet/full_html/2025/01/stet20240285/stet20240285-eq33.gif) and the first and second order partial derivatives of equation (19) with respect to xfi are:

and the first and second order partial derivatives of equation (19) with respect to xfi are:  .

.

Given the conditions (9γ(1 − s) − 2(η + 1)2(h + np0)2)(γ(1 − s) − 2(1 − η)2(h + np0)2) > 0, 9γ(1 − s) − 2(5 − 8η + 5η2)(h + np0)2 > 0, 9γ − 2(2 − β)2(g + p0)2 > 0, H4 is a negative definite matrix, along with  , there exists an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (18) with respect to xei and equation (19) with respect to xfi equal to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be obtained as:

, there exists an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (18) with respect to xei and equation (19) with respect to xfi equal to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be obtained as: (20)

(20)

(21)

(21)

In the first stage, let ∂WSR/∂s = 0, the optimal subsidy rate under strategy R can be defined as: (22)

(22)

4.4 Full coopetition (strategy C)

Under strategy C, in the second stage, both firms simultaneously decide on R&D investments for FVs and NEVs to maximize their joint profits.

In the second stage, firms Mi determine xei and xfi to maximize their joint profits, then the two firms determine the optimal R&D investments as: (23)

(23)

Similarly, given the conditions (9γ(1 − s) − 2(1 + η)2(h + np0)2)(γ(1 − s) − 2(1 − η)2(h + np0)2) > 0, 9γ(1 − s) − 2(5 − 8η + 5η2)(h + np0)2 > 0, (9γ − 2(1 + β)2(g + p0)2)(γ − 2(1 − β)2(g + p0)2) > 0, 9γ − 2(5 − 8β+5β2)(g + p0)2 > 0, The Hessian matrix of equation (23) is a negative definite matrix. There exists an optimal solution. Setting the first-order partial derivatives of equation (23) with respect to xei and xfi equal to 0, then the optimal R&D investments can be solved as: (24)

(24)

(25)

(25)

In the first stage, according to ∂WSC/∂s = 0, the optimal subsidy rate under strategy C can be found to be: (26)

(26)

Under the four strategies, in the second stage of the game, setting s = 0 yields the equilibrium results of different strategies without government subsidies, as shown in Table 2. The equilibrium results for four strategies under the optimal subsidy are shown in Table 3.

The equilibrium results for four strategies without government subsidies.

The equilibrium results for four strategies under the optimal subsidy.

5 Result comparison

5.1 Horizontal comparison

Horizontal comparison refers to the comparative analysis of different strategies within a scenario, including two cases: the scenario without government subsidies and the scenario with government subsidies.

5.1.1 The scenario without government subsidies

(1) Strategy ND(NR) and Strategy NJ(NC)

Proposition 2: The comparison between strategy ND(NR) and strategy NJ(NC) can reveal differences in cooperative R&D for FVs within the context of R&D competition (cooperation) for NEVs without government subsidies:

① For β ∈ [0, 1],  .

.

② If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  , WSNJ < WSND (WSNC < WSNR); otherwise,

, WSNJ < WSND (WSNC < WSNR); otherwise,  ,

,  , WSNJ ≥ WSND (WSNC ≥ WSNR).

, WSNJ ≥ WSND (WSNC ≥ WSNR).

Proposition 2 posits that within the framework of R&D competition (cooperation) in the NEVs sector, government subsidies, R&D investments and outputs in NEVs remain unaffected regardless of whether firms engage in R&D cooperation for FVs. From the perspective of increasing R&D investments and expanding production scale in FVs, when the spillovers level of FVs is low, firms should opt for strategy ND(NR); conversely, when the spillovers level is high, firms should choose strategy NJ(NC). Similarly, this conclusion applies to social welfare considerations. However, from the perspective of maximizing firm profits, strategy NJ(NC) consistently outperforms strategy ND(NR). This suggests that R&D cooperation for FVs yields superior outcomes compared to R&D competition, corroborating findings from numerous studies.

(2) Strategy ND(NR) and Strategy NJ(NC)

Proposition 3: The comparison between strategy ND(NJ) and strategy NR(NC) can indicate differences in cooperative R&D for NEVs within the context of R&D competition (cooperation) for FVs without government subsidies:

① For η ∈ [0, 1], there are  ,

,

.

.

② If 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ,

,  , WSNR < WSND (WSNC < WSNJ); otherwise,

, WSNR < WSND (WSNC < WSNJ); otherwise,  ,

,  , WSNR ≥ WSND (WSNC ≥ WSNJ).

, WSNR ≥ WSND (WSNC ≥ WSNJ).

Proposition 3 indicate that the collaborative efforts in the R&D of NEVs do not significantly impact the R&D investments and outputs of FVs. However, they have a considerable effect on the R&D investments and outputs of NEV, subsequently influencing both corporate profits and societal welfare. Specifically, regarding the R&D investments and outputs of NEV and societal welfare, when the spillovers level of NEVs is low, strategy ND(NJ) is superior to strategy NR(NC). Conversely, when the spillovers level is high, strategy NR(NC) becomes more advantageous than strategy ND(NJ). This insight suggests the complex interplay between collaboration, competition, and innovation in the automotive industry [61]. In terms of corporate profits, for any spillovers level of NEVs, strategy NR(NC) consistently outperforms strategy ND(NJ). This indicates that regardless of whether there is collaborative R&D for fuel vehicles, collaborative R&D in comparison to the competition in NEVs will always enhance corporate profit.

(3) Strategy ND(NJ) and Strategy NC(NR)

Proposition 4: The comparison between Strategy ND and Strategy NC highlights the differences between R&D competition and cooperation for both FVs and NEVs, while the contrast between Strategy NJ and Strategy NR emphasizes the distinctions in R&D collaboration between FVs and NEVs without government subsidies:

① If 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ,

,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  ),

),  ).

).

② If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ),

),  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  ,

,  .

.

③ For η ∈ [0, 1] and β ∈ [0, 1],  . If

. If  ; if

; if

④ If 0 ≤ β < 1/2 and 0 ≤ η < 1/2, WSNC < WSND; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1 and 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1, WSNC ≥ WSND; if 0 ≤ β < 1/2 and 1/2 < η ≤ 1, WSNJ < WSNR; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1 and 0 ≤ η ≤ 1/2, WSNJ ≥ WSN.

Where  ,

,  .

.

Proposition 4 indicates that, in the context of R&D investments and production scale expansion for both FVs and NEVs, the level of technological spillovers significantly influences strategic choices. Specifically, when the spillovers level is low, Strategy ND is more advantageous than Strategy NC; conversely, when the spillovers level is high, Strategy NC outperforms Strategy ND.

In terms of corporate profit, strategy NC consistently outperforms strategy ND, regardless of variations in the level of technology spillover. This finding suggests that cooperation can lead to profit growth for enterprises in the absence of government subsidies. However, the superiority of strategy NR over strategy NJ, or vice versa, depends on the market power of the two types of vehicles. When the market power of FVs is strong, strategy NJ is favored; conversely, when the market power is weaker, strategy NR prevails. This phenomenon reflects the profound impact of market structure and competition intensity on corporate strategies.

From a social welfare perspective, when the spillovers level for both FVs and NEVs are low, Strategy ND is superior to Strategy NC. Conversely, when both spillovers level are high, Strategy NC becomes more favorable. Furthermore, in scenarios where the technology spillover from FVs is low while that from NEVs is high, Strategy NR is preferable to Strategy NJ. Conversely, if FVs have high spillover while NEVs have low spillover, Strategy NJ outperforms Strategy NR. These findings underscore the nuanced interplay between technology spillover levels and strategic choices, highlighting their critical implications for optimizing social welfare in the automotive sector.

(4) Comprehensive comparison

The previous section compared the differences between the two strategies, this section undertakes a comprehensive comparative analysis of all four strategies to present the optimal competitive strategy for the firms. This synthesis leads to Proposition 5.

Proposition 5: The comprehensive comparison of the four strategies without government subsidies yields the following results:

① If 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  .

.

② If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ; otherwise

; otherwise

.

.

③ For 0 ≤ β ≤ 1 and 0 ≤ η ≤ 1,  .

.

④ If 0 ≤ β < 1/2 and 0 ≤ η < 1/2, WSND > max{WSNJ, WSNR} > min{WSNJ, WSNR} > WSNC; if 0 ≤ β < 1 and 1/2 < η ≤ 1, WSNR > max{WSND, WSNC} > min{WSND, WSNC} > WSNJ; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1 and 0 ≤ η ≤ 1/2, WSNJ ≥ max{WSND, WSNC} ≥ min{WSND, WSNC} ≥ WSNR; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1 and 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1, WSNC ≥ max{WSNJ, WSNR} ≥ min{WSNJ, WSNR} ≥ WSND.

Proposition 5 indicates that in the absence of government subsidies, there is no significant difference between strategies ND and NJ regarding the increase in R&D investments and outputs of NEVs, nor is there a significant difference between strategies NC and NR. When the spillovers level of NEVs is low, strategies ND(NJ) are superior to strategies NC(NR). Conversely, when the spillovers level is high, strategies NC(NR) outperform strategies ND(NJ). Regarding the increase in R&D investments and outputs of FVs, there is no significant difference between strategies ND and NR, and between strategies NC and NJ. When the spillovers level of FVs is low, the former outperforms the latter. However, when the spillovers level is high, the latter outperforms the former.

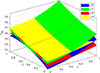

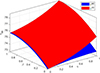

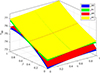

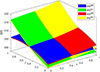

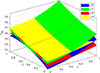

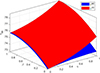

In terms of corporate profit, regardless of the spillovers level, strategy NC is superior to both strategies NR and NJ, while strategies NR and NJ are superior to strategy ND, as shown in Figure 2. This indicates that strategy NC has a sustained competitive advantage in achieving corporate profits. From the perspective of social welfare, as shown in Figure 3, when both the spillovers levels of FVs and NEVs are low, strategy ND is the optimal strategy. When the spillovers level of FVs is low and that of NEVs is high, strategy NR is the optimal strategy. When the spillovers level of FVs is high and that of NEVs is low, strategy NJ is the optimal choice. Finally, when the spillovers levels for both are high, strategy NC is deemed the optimal strategy. These findings underscore the critical influence of spillover levels on strategic decision-making within the automotive sector, highlighting the importance of tailoring strategies to specific technological contexts to enhance overall social welfare.

|

Fig. 2 The comparison of corporate profit under four strategies without subsidies. |

|

Fig. 3 The comparison of social welfare under four strategies without subsidies. |

5.1.2 The scenario with government subsidies

(1) Strategy YD(YR) and Strategy YJ(YC)

Proposition 6: The comparison between strategy YD(YR) and strategy YJ(YC) can reveal differences in cooperative R&D for FVs in the context of R&D competition (cooperation) for NEVs under optimal subsidies:

① For β ∈ [0, 1], sYJ = sYD (sYC = sYR),  ).

).

② If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ,

,  , WSYJ < WSYD (WSYC < WSYR); otherwise,

, WSYJ < WSYD (WSYC < WSYR); otherwise,  ,

,  , WSYJ ≥ WSYD (WSYC ≥ WSYR).

, WSYJ ≥ WSYD (WSYC ≥ WSYR).

Proposition 6 posits that within the framework of R&D competition (cooperation) in the NEVs sector, government subsidies, R&D investments and outputs in NEVs remain unaffected regardless of whether firms engage in R&D cooperation for FVs. From the perspective of increasing R&D investments and expanding production scale in FVs, when the spillovers level of FVs is low, firms should opt for strategy YD(YR); conversely, when the spillovers level is high, firms should choose strategy YJ(YC). Similarly, this conclusion applies to social welfare considerations. However, from the perspective of maximizing firm profits, strategy YJ(YC) consistently outperforms strategy YD(YR). This finding is consistent with the scenario of no government subsidies, indicating that government subsidies do not have an impact on the decision-making behavior concerning fuel vehicles.

(2) Strategy YD(YJ) and Strategy YR(YC)

Proposition 7: The comparison between strategy YD(YJ) and strategy YR(YC) can indicate differences in cooperative R&D for NEVs in the context of R&D competition (cooperation) for FVs under optimal subsidies:

① For η ∈ [0, 1], there are  ,

,  ),

),  (

( ),

),  (

( ), WSYR = WSYD (WSYC = WSYJ).

), WSYR = WSYD (WSYC = WSYJ).

② If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, sYR > sYD (sYC > sYJ),  (

( ); otherwise, sYR ≤ sYD (sYC ≤ sYJ),

); otherwise, sYR ≤ sYD (sYC ≤ sYJ),  .

.

From Proposition 7, it is evident that whether firms are incentivized to participate in R&D cooperation for NEVs within a R&D competitive (or cooperative) environment for FVs depends on the level of technology spillovers of NEVs. However, irrespective of whether the two firms engage in R&D cooperation for NEVs, their optimal R&D investments and outputs for both FVs and NEVs, as well as societal welfare, remain unchanged. The rationale lies in the distinct markets for both vehicle types. The decision to engage in R&D cooperation for NEVs does not influence firms’ decisions regarding R&D investments and production of FVs. At the same time, governmental subsidy policies can incentivize firms to maintain optimal R&D investments in NEVs at a consistent level without impacting societal welfare. This discovery challenges the prevailing belief that cooperation consistently results in superior results. The importance of firms carefully evaluating factors such as R&D spillovers and government subsidies when choosing their coopetition strategies is highlighted, rather than automatically opting for cooperative approaches [45]. In intricate innovation ecosystems, competitive strategies can sometimes lead to better overall outcomes, particularly when the spillovers level is high and subsidy policy is present, as emphasized by the proposition.

(3) Strategy YD(YJ) and Strategy YC(YR)

Proposition 8: The comparison of Strategy YD and Strategy YC illustrates distinctions between R&D competition and R&D cooperation for both FVs and NEVs, whereas the contrast between Strategy YJ and Strategy YR highlights the differences in R&D collaboration between FVs and NEVs under optimal subsidies:

① If η ∈ [0, 1] and β ∈ [0, 1],

② If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, sYC > sYD (sYR > sYJ); otherwise, sYC ≤ sYD (sYR ≤ sYJ).

③ If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ,

,  WSYC < WSYD (WSYJ < WSYR); otherwise,

WSYC < WSYD (WSYJ < WSYR); otherwise,  ),

),  , WSYC ≥ WSYD (WSYJ ≥ WSYR).

, WSYC ≥ WSYD (WSYJ ≥ WSYR).

④ For β < 1/2, if 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ), otherwise,

), otherwise,  ). For β ≠ 1/2, if y2 > |y3|,

). For β ≠ 1/2, if y2 > |y3|,  ), otherwise when 0 ≤ η < 1/2,

), otherwise when 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ), when 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

), when 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  ). Where

). Where  .

.

From Proposition 8, the R&D investments and outputs for NEVs remain constant regardless of whether there is R&D cooperation between FVs and NEVs, attributable to the incentive effect of government subsidy behavior. However, the intensity of government subsidies between strategies depends on the spillovers level of NEVs. Specifically, when the spillovers level is low, the government provides a higher subsidy rate to strategy YC(YR); conversely, when the spillovers level is high, strategy YD(YJ) receives greater government support.

From the perspective of increasing R&D investments and outputs for FVs, firms should opt for strategy YD(YR) when the spillovers level of FVs is low. Conversely, when the spillovers level of FVs is high, firms are advised to adopt strategy YC(YJ). Technology spillovers of FVs play an equally significant role in social welfare. However, changes in corporate profits are influenced by several variables, including DCP, dual technology spillovers, consumer preferences, and R&D efficiency. Overall, when the spillovers level of FVs meets a specified threshold, the optimal profits are achieved under strategy YC(YR) under conditions of low spillovers level of NEVs. Conversely, strategy YD(YJ) yields superior profits. It is noteworthy that when the spillovers level of FVs takes a more general case, if the spillovers level of NEVs is low (high), the enterprise chooses strategy YC(YJ) profit is always better than strategy YD(YR).

(4) Comprehensive comparison

The previous section compared the differences between the two strategies, this section undertakes a comprehensive comparative analysis of all four strategies to present the optimal competitive strategy for the firms.

Proposition 9: The comprehensive comparison of the four strategies with government subsidies yields the following results:

① If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, sYR = sYC > sYD = sYJ; otherwise, sYR = sYC ≤ sYD = sYJ.

② If 0 ≤ β ≤ 1, and 0 ≤ η ≤ 1  ,

,  .

.

③ For 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ,

,  WSYD = WSYR > WSYJ = WSYC; otherwise,

WSYD = WSYR > WSYJ = WSYC; otherwise,  ,

,  , WSYD = WSYR ≤ WSYJ = WSYC.

, WSYD = WSYR ≤ WSYJ = WSYC.

④ For β = 1/2, if 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ; if, 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

; if, 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  ). For β ≠ 1/2, if 0 ≤ η < 1/2,

). For β ≠ 1/2, if 0 ≤ η < 1/2,  ; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  .

.

Proposition 9 demonstrates that the R&D investments and outputs of NEVs remain unchanged under the optimal subsidy, irrespective of the competitive strategy chosen by firms. Optimal government subsidies depend on the spillovers level of NEVs. When the spillovers level is low, firms opt for R&D cooperation strategies (Strategies YR and YC), thereby qualifying for higher subsidy rates. Conversely, when the spillovers level is high, firms should pursue R&D competition strategies for NEVs (Strategies YD and YJ). Regarding the enhancement of R&D investments and the expansion of production scales for FVs, firms should opt for Strategies YD and YR when the spillovers level is low. Conversely, when the spillovers level is high, they should adopt Strategies YJ and YC. Moreover, the optimal strategy chosen by firms significantly contributes to improving social welfare. From the perspective of maximizing corporate profit, as depicted in Figure 4, in general, firms can achieve this goal by selecting Strategy YC when the spillovers level of NEVs is low. Conversely, Strategy YJ tends to maximize their profits.

|

Fig. 4 The comparison of corporate profit under four strategies with optimal subsidies |

Numerous studies have demonstrated that cooperative strategies usually sustain high system performance, whereas competitive strategies sometimes result in performance decline due to conflicts between individual and collective rationality. However, in the presence of R&D spillovers and government subsidies, this general conclusion may no longer hold. This indicates that competitive firms should not blindly pursue cooperation, as it may lead to profit losses.

In general, the optimal competitive strategy chosen by firms for profit maximization also leads to optimal government subsidies. However, it is noteworthy that the R&D investments and outputs of NEVs remain unchanged across various competitive strategies, impacting only the R&D investments and outputs of FVs, as well as social welfare. Therefore, to achieve dual enhancement in both the economic and social performance of firms, it is crucial to maintain a higher spillovers level of FVs.

5.2 Vertical comparison

The vertical comparison refers to the differential analysis between the same strategies in scenarios with and without government subsidies.

Proposition 10: The comparison of the four strategies under scenarios without government subsidies and with government subsidies can be obtained as:

① (a)  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , WSYD > WSND.

, WSYD > WSND.

(b) If 0 ≤ η < η1,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  .

.

② (a)  ,

, ,

,  ,

,  , WSYJ > WSNJ.

, WSYJ > WSNJ.

(b) If 0 ≤ η < η1,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  .

.

③  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , WSYR > WSNR.

, WSYR > WSNR.

④  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  , WSYC > WSNC.

, WSYC > WSNC.

Where η1 satisfies  .

.

Proposition 10 posits that, irrespective of the competitive strategies adopted by firms, government subsidies exert no significant influence on the R&D investments and outputs of FVs. In contrast, these subsidies play a substantial role in stimulating R&D investments in NEVs. By incentivizing companies to scale up their production of NEVs, government subsidies contribute to enhanced social welfare outcomes. This is because the subsidies lower the R&D costs of NEVs, encouraging firms to increase their investments in this area. Higher R&D investments enhance the range capacity of NEVs, thereby strengthening consumers’ willingness to purchase. This virtuous mechanism prompts companies to further expand their production scale, achieving a significant Pareto improvement in social performance. Simultaneously, government subsidies markedly bolster corporate profits under strategies YR and YC. In contrast, the influence of government subsidies on corporate profits under strategies YD and YJ is contingent upon the level of technological spillovers of NEVs. Specifically, when the spillovers level is low, government subsidies may lead to a decrease in profits for these two strategies; conversely, it is only when the spillovers level is high that government subsidies can effectively promote profit growth (Fig. 5). This phenomenon can be attributed to the influence of technological spillovers on corporate innovation capabilities and market competitiveness. When the spillovers level is low, firms may struggle to fully leverage government subsidies to drive technological advancement or enhance efficiency, resulting in reduced profits. In such cases, subsidies might be allocated to short-term operational or maintenance costs, failing to translate into a sustainable competitive advantage. However, when the spillovers level is high, firms can absorb and apply external technological advancements, thereby strengthening their R&D capabilities. This leads to improvements in production efficiency and product innovation, enabling government subsidies to be more effectively converted into profit growth, thus fostering the long-term development of firms in the market.

|

Fig. 5 The comparison of corporate profit under strategy YD with and without subsidies. |

6 Analysis of impact factors

Based on the comparative analysis presented earlier, it is evident that firms’ optimal choices tend to concentrate on strategy J and strategy C. Therefore, this section centers on examining the effects of parameters related to FVs, NEVs, and shared parameters on R&D investments, outputs, profits, and social welfare under these optimal strategies.

6.1 Impact of FVs related parameters

Corollary 1: Under the optimal strategy, firms’ FVs R&D investments, outputs, profits and social welfare vary with the spillovers level of FVs (β), consumers’ low-carbon preference (g), the requirement for the proportion of NEVs credits (λ), and the difference between actual and standard values of the average 100-km fuel consumption (μ) as:

① (a) ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

(b) If 0 ≤ β < 1/2,  ,

,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  ,

,  .

.

(c) If 0 ≤ β ≤ 1/2,  ,

,  ; otherwise, when γ0 < γ < γ1,

; otherwise, when γ0 < γ < γ1,  ,

,  , when γ ≥ γ1,

, when γ ≥ γ1,  ,

,  .

.

(d) If 0 ≤ β ≤ 1/2,  ,

,  ; if 1/2 < β < 4/5, when γ0 < γ < γ2,

; if 1/2 < β < 4/5, when γ0 < γ < γ2,  ,

,  , otherwise,

, otherwise,  ,

,  ; if 4/5 ≤ β ≤ 1,

; if 4/5 ≤ β ≤ 1,  ,

,  .

.

② (a) ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

(b) If 0 ≤ β ≤ 1/2, when γ0 < γ < γ3,  ,

,  , otherwise,

, otherwise,  ,

,  ; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1,

; if 1/2 ≤ β ≤ 1,  ,

,  .

.

③  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

, ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

④  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Corollary 1 indicates that the level of technology spillover of FVs has a significantly divergent impact on equilibrium outcomes depending on the strategic approach adopted. Under collaborative R&D strategies for FVs (Strategies YJ and YC), firms experience an increase in R&D investments, outputs, profits, and social welfare as the spillovers level of FVs rises. Conversely, the impact of technology spillovers on variables associated with competitive R&D strategies for FVs (Strategies YD and YR) presents a more nuanced and varied trend. First, under Strategies YD and YR, R&D investments in FVs decline as the level of technology spillover increases. This counterintuitive observation may stem from the fact that higher spillovers level reduce the incentive for competing firms to invest in R&D. Second, when the spillovers level is low, outputs of FVs under strategies YD and YR increases with rising spillover levels. However, when the spillovers level is high, the outputs under these strategies decrease as the spillover increases. This dual effect of technology spillover on production output is detailed in Proposition 1. Third, when the spillovers level is low, profits for firms under Strategies YD and YR increase with higher spillover levels. In contrast, when the spillovers level is high, lower R&D efficiency results in profits under Strategies YD and YR continuing to rise with increasing spillover levels, while higher R&D efficiency may lead to a decline in profits as spillover levels rise. This phenomenon reflects the complex interplay between R&D efficiency, market competition, enterprise costs, and market demand. Finally, concerning social welfare, when the spillovers level is low, social welfare under Strategies YD and YR improves as spillover levels increase. At moderate levels of spillover, lower R&D efficiency enhances social welfare as spillover increases, whereas higher R&D efficiency may lead to a reduction in social welfare despite increasing spillover levels. When the spillovers level is high, social welfare under these strategies also decreases with rising spillover levels. This phenomenon may be attributed to excessively high technology spillover levels inhibiting competing firms’ R&D investments and production enthusiasm, ultimately leading to a detriment in social welfare. In summary, the aforementioned conclusion underscores the complexity and strategic dependence of the effects of technology spillover on various performance metrics of firms. It highlights the diverse implications of spillover effects on economic outcomes across different strategic choices.

Similarly, consumer preference for low-carbon products significantly promotes the growth of enterprises in terms of research and development (R&D) investment, production volume, profits, and social welfare under strategies YJ and YC. In the context of strategies YD and YR, although there is an increase in R&D investment, production volume, and social welfare related to fuel vehicles as consumer low-carbon preferences rise, the changes in enterprise profits present a more complex scenario. Specifically, when the level of technology spillover for fuel vehicles is low, the R&D efficiency of enterprises is also low, which results in an increase in profits under strategies YD and YR in response to heightened consumer low-carbon preferences. Conversely, when R&D efficiency is high, profits under strategies YD and YR may decline as consumer low-carbon preferences increase. This phenomenon may arise from the tendency of firms with high R&D efficiency to overly focus on technological innovation and product optimization in their pursuit of profits, which can slow down their market response and cause them to miss opportunities to capitalize on the market potential associated with consumer low-carbon preferences. In other words, achieving a balance between technological innovation and market demand is crucial for enterprises; excessive technological investment may hinder their ability to meet consumer needs in a timely manner. When the level of technology spillover for fuel vehicles is high, profits under strategies YD and YR similarly increase alongside rising consumer low-carbon preferences. This outcome indicates that a high level of technology spillover enhances firms’ responsiveness to market demands, enabling them to adapt to consumer preferences for low-carbon products while simultaneously achieving higher profit levels. This may be due to the rapid dissemination of technology, allowing firms to adjust product characteristics quickly to better satisfy consumer low-carbon requirements, thereby enhancing their market competitiveness and profitability.

Conversely, regardless of the competitive and cooperative strategies adopted by enterprises, R&D investment, production volume, profits, and social welfare associated with fuel vehicles decrease as the requirements for the proportion of NEV credits and the disparity between the actual and benchmark fuel consumption per 100 kilometers increase. This phenomenon occurs because higher requirements for NEV credit proportions, along with a greater discrepancy between actual and benchmark fuel consumption, impose greater pressure on enterprises to meet credit demands. To alleviate this pressure, firms may reduce the production of fuel vehicles, which in turn leads to a decline in profits and a reduction in social welfare. This indicates that under the dual credit policy, increasing the requirements for NEV credit proportions and reducing the fuel consumption of fuel vehicles per 100 kilometers will not effectively incentivize enterprises to enhance their R&D investments in fuel vehicles; rather, it may solely result in a decrease in the production quantity of fuel vehicles. Therefore, policymakers must carefully consider the impact of incentive measures on corporate production decisions and the relationship between market supply and demand when designing such policies.

6.2 Impact of NEVs related parameters

Corollary 2: According to the optimal strategy, firms’ NEVs R&D investments, outputs, profits, and social welfare vary with the levels of NEVs technology spillovers (η), consumer range preference (h), and NEVs credits accounting coefficients (n) as follows:

① (a) ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

(b) If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, when γ0 < γ < γ5,  ,

,  , otherwise,

, otherwise,  ,

,  ; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  ,

,  .

.

② (a) ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

(b) If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, when γ0 < γ < γ6, ,

,  , otherwise,

, otherwise, ,

,  ; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  ,

,  .

.

③ (a) ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

(b) If 0 ≤ η < 1/2, when γ0 < γ < γ6,  ,

,  , otherwise,

, otherwise,  ,

,  ; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,

; if 1/2 ≤ η ≤ 1,  ,

,  .

.

Where  ,

,  .

.

Corollary 2 illustrates that under the optimal strategy, regardless of the competitive or cooperative strategies adopted by firms, NEVs’ R&D investments, outputs, and social welfare significantly increase with higher levels of technology spillovers, consumer range preferences, and the credits accounting coefficient. In the context of cooperative R&D strategies of NEVs (i.e., strategies YR and YC), corporate profits also rise in tandem with increases in the aforementioned three factors. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that R&D collaboration facilitates the internalization of the externalities associated with technology spillovers, thereby enhancing firms’ enthusiasm for R&D activities. Elevated levels of technology spillover, consumer preferences for extended range, and higher accounting coefficients incentivize firms to increase their R&D investments, expand production scales, and subsequently achieve profit growth.

However, under strategies YD and YJ, the relationship between corporate profits and the levels of technology spillover, consumer range preferences, and accounting coefficients demonstrates a degree of complexity. Specifically, when the level of technology spillover in the EV sector is low, higher R&D efficiency may lead to a decrease in corporate profits as the levels of technology spillover, consumer range preferences, and accounting coefficients increase. This counterintuitive outcome can be explained by the fact that, although higher R&D efficiency tends to reduce research costs, firms in low spillover environments often adopt more conservative R&D strategies, focusing resources on enhancing their proprietary technologies. While this approach may improve a firm’s technological capabilities in the short term, it can also intensify market competition, thereby compressing profit margins.

Conversely, firms with lower R&D efficiency may adopt more flexible strategies in a competitive market, allowing them to achieve a certain market share and profit growth with lower R&D investments. This flexibility enables firms to better adapt to changes in market demand, particularly in highly competitive environments. When the level of technology spillover is high, profits for firms using strategies YD and YJ tend to increase significantly with rising levels of technology spillover, consumer range preferences, and accounting coefficients. This observation indicates that, in environments characterized by high technology spillovers, firms are better positioned to leverage external knowledge and resources, thereby enhancing their competitive advantages and profitability.

6.3 Impact of common parameters of FVs and NEVs

Corollary 3: The equilibrium outcomes for both FVs and NEVs are influenced by the proportion of potential demand for NEVs (θ), and the price of credits (p0) as follows:

① (a) ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, .

.

(b) If ξ1 < ξ3 (ξ1 < ξ4),  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  . If ξ2 < ξ3 (ξ2 < ξ4),

. If ξ2 < ξ3 (ξ2 < ξ4),  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  . If ξ2 < ξ3 (ξ3 < ξ5),

. If ξ2 < ξ3 (ξ3 < ξ5),  ,

,  ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  ,

,  .

.

② (a) ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, .

.

(b) If 0 < θ < θ1 (0 < θ < θ2),  ,

, ; otherwise,

; otherwise,  ,

, (

( ,

, ). If 0 < θ < θ3 (0 < θ < θ4),

). If 0 < θ < θ3 (0 < θ < θ4),  ,

, (

( ,

, ); otherwise,

); otherwise,  ,

, (

( ,

, ).

).

(c) For 0 ≤ η < 1/2, if 0 < θ < θ5,  ; otherwise, if

; otherwise, if  ,

,  , if

, if  ,

,  . For 1/2 ≤η ≤ 1, if 0 < θ < θ5,

. For 1/2 ≤η ≤ 1, if 0 < θ < θ5,  ; otherwise, if

; otherwise, if  ,

,  , if

, if  ,

,  .

.

(d) For 0 < θ < θ6,  ,

,  ; otherwise, if

; otherwise, if  ,

,  ,

,  , if

, if  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Where  ,

,  ,

, ,

,  ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

,  ,

, , ϕ9 = a(1 − θ) + g(λ + μ).

, ϕ9 = a(1 − θ) + g(λ + μ).

Corollary 3 displays that whether the enterprise opts for competitive or cooperative strategies, as the proportion of potential demand for NEVs grows, the demand scale for NEVs expands while that for FVs contracts. During this shift, R&D investments and outputs of NEVs increase while those for FVs decrease. This underscores the pivotal role of market size in shaping firms’ decisions on R&D investments and outputs. It is noteworthy that the proportion of potential demand for NEVs exerts opposing effects on the profits of FVs (negative) and NEVs (positive). Therefore, overall profit increases only when the positive effect outweighs the negative effect; conversely, profits decrease. Similarly, the social welfare has a similar nature.

Under the optimal subsidy policy, as the price of credits increases, R&D investments and outputs of NEVs are expected to rise. However, there is uncertainty regarding the changes in R&D investments and outputs of FVs. Specifically, when the proportion of potential demand for NEVs is small – indicating a large market demand for FVs – the increase in credit price motivates firms to boost R&D investments in FVs and expand production. Conversely, when market demand for FVs is insufficient, firms may lack the incentive to invest in R&D. In such cases, a higher credit price could compel firms to scale back production capacity instead.

The impact of credit prices on firms’ profits is notably intricate due to the dual components that constitute total profits: profits from FVs and NEVs. While NEVs profits tend to increase with credit prices under the optimal strategy (strategy YJ or strategy YC), the relationship between FVs profits and credit prices is more nuanced, exhibiting both positive and negative aspects. Overall, when the potential demand for NEVs is limited, firms’ profits under the optimal strategy generally rise with higher credit prices. Conversely, the effect of credit prices on corporate profits hinges on balancing the positive impact on NEVs profits against the negative impact on FVs profits. Firms’ profits increase with higher credit prices only when the former outweighs the latter; otherwise, profits decrease. Similar observations extend to social welfare, reflecting analogous dynamics. Consequently, government attention must focus on the scale of demand for both FVs and NEVs. Firms’ profits and social welfare will only increase alongside rising credit prices if FVs maintain a significant market size or if the influence of credit prices on NEVs surpasses their effect on FVs. Otherwise, higher credit prices do not necessarily enhance economic or social performance.

7 Discussion

This study investigates manufacturers’ coopetition strategies within the framework of the DCP, taking into account consumer preferences and government subsidies. The results align with previous research, including Li and Xiong [31] and Li et al. [32], regarding the DCP’s impact on FVs and NEVs, thereby affirming the policy’s effectiveness in promoting the growth of NEVs. However, this investigation offers a deeper understanding by revealing that the DCP’s effects on FVs are more intricate than previously recognized. Contrary to expectations, stricter credit requirements and greater discrepancies between actual and standard fuel consumption values do not necessarily incentivize investments in fuel-saving R&D. Instead, these factors may lead to a decline in the production and sales of FVs. This highlights the need for policy refinement to better harmonize the transition toward NEVs with the continuous improvement of FV efficiency [62, 63].

The optimal government subsidy rate under the DCP, as explored in the second research question, reveals a more complex relationship with firm strategies than previously anticipated. The findings build upon the work of Bronzini and Piselli [46] and Chen et al. [48] by demonstrating that subsidies effectively enhance R&D in NEV range technology without inducing a crowding-out effect. This result is particularly significant, as it challenges earlier concerns expressed in the literature regarding the potentially detrimental impacts of government subsidies on private R&D investments. An examination of firms’ optimal cooperation strategies and incentives under the DCP uncovers unexpected patterns. While prior studies, such as those by Kamien et al. [18] and D’Aspremont and Jacquemin [40], generally advocated for cooperative R&D strategies, our findings indicate that the optimal approach is dependent on the degree of technology spillovers. This insight contributes to the existing literature on R&D cooperation and competition, underscoring the importance of considering industry-specific factors when determining an appropriate strategy.